Avoiding Puppeteer Antipatterns

Let's examine common Puppeteer practices that might be harming your web scraping and browser automation scripts.

Table of contents

- Overusing waitForTimeout

- Assuming Puppeteer's API works like the native browser API

- Never using "domcontentloaded"

- Not blocking images and resources

- Avoiding page.evaluate when trusted events aren't necessary

- Misusing developer tools-generated selectors

- Not using the return value of .waitForSelector and .waitForXPath

- Using a separate HTML parser with Puppeteer

- Using Puppeteer when other tools are more appropriate

- Wrapping up

Puppeteer is a popular browser automation library for NodeJS commonly used for web scraping and end-to-end testing. Since Puppeteer offers a rich API that performs complex interactions with the browser in real-time, there's plenty of room for misunderstandings and antipatterns to creep into your scripts.

In this post, we'll share 9 Puppeteer antipatterns I've used or seen in Puppeteer code over the past few years. While the list isn't exhaustive, we hope it'll elevate your understanding and appreciation of the tool.

I've assumed that readers arrive with a working familiarity with Puppeteer and have written at least a few scripts with it, enough to have encountered some of the quirks and pitfalls of automation.

Overusing waitForTimeout

Puppeteer's readme says it best:

Puppeteer has event-driven architecture, which removes a lot of potential flakiness. There's no need for evil

sleep(1000)calls in puppeteer scripts.

The trouble is, Puppeteer has page.waitForTimeout(milliseconds), identical semantics to the evil sleep(1000) call! It can be handy to have this escape hatch in the API, but it's also easy to abuse.

Sleeping is evil because it introduces a race condition that involves two possible outcomes.

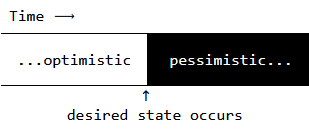

Sleeping causes a race condition between the browser state and the Puppeteer driver

One outcome is when the sleep duration is too optimistic and the driver wakes up before the browser is in the desired state. In this case, the issue is correctness: the driver will likely wind up missing data from responses that haven't arrived, or throw errors when attempting to manipulate elements that don't exist.

The other outcome is when the sleep duration is too pessimistic and the browser reaches the desired state before the driver wakes up. In this case, the issue is efficiency: elapsed time between the desired state appearing and the driver waking up is wasted. Even a small extra delay becomes painful when incurred repeatedly, such as during automated testing.

Furthermore, a sleep that seems to work can create an illusion of robustness. A duration that's long enough today might be too short tomorrow. Sleeping introduces an overfitted, environment-specific value that may work on one machine, but can easily fail on another. That other machine is often a production deploy on the cloud, where debugging discrepancies against a working local version can be difficult.

The alternatives to waitForTimeout include waitForSelector, which blocks until a selector appears, or the more general waitForFunction, which blocks until a predicate condition becomes true. Puppeteer tests the condition in a tight requestAnimationFrame loop or upon DOM changes with a MutationObserver. Both waitForSelector and waitForFunction adhere to the event-driven model and eliminate race conditions.

There are plenty of occasions when page.waitForTimeout is appropriate, however. It can help with debugging, throttling interaction to simulate human behavior, rate limiting polling of a resource and as a last resort for handling pesky situations that don't respond well to other approaches. But sleeping as the default option when it's entirely possible to block on an explicit predicate is an antipattern.

Assuming Puppeteer's API works like the native browser API

Puppeteer's API has different semantics from the native browser API. For example, Puppeteer's page.click() seems like a straightforward wrapper on the browser's native HTMLElement.click(), but it actually operates quite differently and hides a fair amount of complexity under the hood.

Instead of invoking the click event handler directly on the element as the native .click() does, clicking in Puppeteer scrolls the element into view, moves the mouse onto the element, presses one of a few mouse buttons, optionally triggers a delay, then releases the mouse button. You can also trigger multiple clicks. In other words, Puppeteer performs a click like a human would.

Neither approach is better, but it's a mistake to assume they're the same and indiscriminately use one or the other across the board.

There are times when using the native browser click makes it possible to access an element the mouse is unable to reach via Puppeteer's click, such as when another element is on top of it. In other cases, such as testing, it's desirable to click with the mouse as a human would, using a trusted event. Puppeteer's docs state:

For automation purposes it's important to generate trusted events. All input events generated with Puppeteer are trusted and fire proper accompanying events. If, for some reason, one needs an untrusted event, it's always possible to hop into a page context with

page.evaluateand generate a fake event:

await page.evaluate(() => {

document.querySelector('button[type=submit]').click();

});

The difference in behavior might be most noticable for page.click(), but it's worth keeping the distinction in mind when working with the rest of Puppeteer's API.

Never using "domcontentloaded"

The default event for Puppeteer's navigiation API, such as page.goto(url, {waitUntil: "some event"}), is {waitUntil: "load"}. I'm guilty of blindly relying on this default without questioning its implications, but it's worth investigating a bit relative to other options: "domcontentloaded", "networkidle2" and "networkidle0".

The

loadevent is fired when the whole page has loaded, including all dependent resources such as stylesheets and images. This is in contrast toDOMContentLoaded, which is fired as soon as the page DOM has been loaded, without waiting for resources to finish loading.

Waiting for load is a useful choice in scenarios where it's important to see the page as the user would. Example use cases include snapping screenshots or generating PDFs. "networkidle0" and "networkidle2" resolve the navigation promise when no more than 0 or 2 network requests are active in the past 500 milliseconds. These settings have similar use cases as "load" and offer more control for handling pages that might keep a polling connection or two active after load, or when the driver needs to flush requests before proceeding.

On the other hand, if the goal is to scrape a table of text statistics that arrives from a network request, there's no sense in waiting around for anything more than "domcontentloaded" and the lone data request, which might look like:

await page.goto(url, {waitUntil: "domcontentloaded"});

const el = await page.waitForSelector(yourSelector, {visible: true});

const data = await el.evaluate(el => el.textContent);

...where yourSelector won't be injected into the page until the desired data arrives.

Not blocking images and resources

If the goal is to scrape a simple piece of data, there's no sense in wasting time and bandwidth requesting all images, stylesheets and/or scripts on a page. When possible, consider disabling JS with page.setJavaScriptEnabled(false), stopping the browser with page.evaluate(() => window.stop()) or enabling request interception to block images as follows:

await page.setRequestInterception(true);

page.on("request", req => {

if (req.resourceType() === "image") {

req.abort();

}

else {

req.continue();

}

});

This helps keep your scripts snappy and reduces waste.

As an aside, there's no need to await page.on, which is strictly callback-driven and does not return a promise. Nonetheless, it can be handy to promisify page.on so results can be awaited later. While most events are available in a promise-based function, others such as "dialog" aren't.

You can use .once and .off methods to ensure the handler is removed when no longer needed.

Avoiding page.evaluate when trusted events aren't necessary

One can easily wind up frustrated when refactoring working browser console code using jQuery or vanilla JS to Puppeteer's trusted interface: page.$, page.$eval, page.type, page.click, and so on. This is a common situation since experimenting with the DOM in the browser console is a typical first step in building a Puppeteer script. These refactors often go sour when attempting to pass complex structures such as ElementHandles between the browser and Node contexts, or encountering behavioral differences in methods like page.click(), discussed above.

Puppeteer provides page.evaluate() as a highly-generalized function to run code in the browser. It supports passing serializable data and returning deserialized results. For times when trusted events aren't needed, plopping a chunk of working browser code inside a page.evaluate and letting it handle the heavy lifting alleviates the time spent on a rewrite and helps mitigate the potential for subtle regressions.

Misusing developer tools-generated selectors

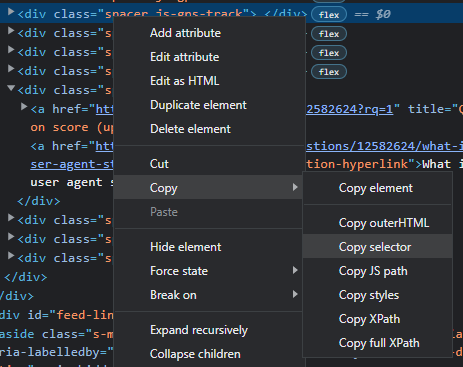

The developer tools in modern browsers let you copy CSS selectors and XPaths to the clipboard easily:

Copying an element's CSS selector in Chrome

This is a boon for developers who might not be familiar with CSS selectors or XPath, and can save time for those who are.

The problem is, these selectors and paths can be overly-rigid and lead to brittle scripts that break if a wrapper is added as a parent further up the tree, or a sibling element shows up unexpectedly after an interaction on the page.

For example, Chrome gives the very strict CSS selector #answer-60796572 > div > div.answercell.post-layout--right > div.s-prose.js-post-body > pre when #answer-60796572 pre might be more resilient to handling dynamic behavior.

Choosing how to select elements is an art, not a science. It takes time to build a feel for which specificity is appropriate for a particular use case. The browser-generated selectors and paths are handy, but are ripe for misuse. When using these selectors, it's wise to take a step back and consider the broader context such as site-specific behavior and script goals.

SerpAPI's post Web Scraping with CSS Selectors using Python provides a nice introduction to CSS selectors in a web scraping context. (Python isn't essential to the selector information.)

Not using the return value of .waitForSelector and .waitForXPath

A common, albeit minor, antipattern is to make an extra call to retrieve an element after waiting for it:

await page.waitForSelector(selector);

const elem = await page.$(selector);

// or:

await page.waitForXPath(xpath);

const [elem] = await page.$x(xpath);

Cleaner and more precise is to use the return value of the waitFor calls:

const elem = await page.waitForSelector(selector);

// or:

const elem = await page.waitForXPath(xpath);

Once you've obtained the ElementHandle, you can use elem.evaluate(el => el.textContent) rather than page.evaluate(el => el.textContent, elem). See a Stack Overflow answer of mine for details on passing nested ElementHandles back to the browser.

Using a separate HTML parser with Puppeteer

Puppeteer already has access to the full power of browser JS and operates on the page in real-time, so it's an antipattern to bring in a secondary HTML parser like Cheerio without good reason. Using Cheerio with Puppeteer involves taking serialized snapshots of the entire DOM (i.e. using page.content()), then asking Cheerio to re-parse the HTML before being able to make a selection. This can be slow, adds a potentially confusing layer of indirection between the live page and the separate HTML parser and creates an additional opportunity for misunderstanding the state of the application.

This approach can be beneficial for debugging and when HTML snapshots or particular features of Cheerio are needed (like sizzle selectors), but the common case is to use Puppeteer on its own.

Using Puppeteer when other tools are more appropriate

Web browser automation is a heavy and slow proposition. It involves launching a browser process, then making network calls to navigate the browser to a page, then manipulating the page to accomplish a goal. Sometimes that goal can be achieved directly using a simple HTTP request to a public API or retrieving data baked into a page's static HTML. Using a request library like fetch and an HTML parser like Cheerio, when possible, can be a faster and easier method than Puppeteer.

When collecting requirements for a scraping task, take the time to make sure the data isn't hidden in plain sight. This usually involves viewing the page source to see the static HTML and analyzing network traffic using the browser's developer tools to determine where the data you're after is coming from. Reading the website's FAQ and documentation often points to a public API. Occasionally, other sites offer the same information in a more accessible format.

For one-time scrapes, I'll often select the data we need using browser JS and copy it to the clipboard from the console by hand instead of reaching for Puppeteer. Userscripts, extensions and bookmarklets are other lightweight ways to manipulate a page without Puppeteer or Node.

While these alternatives might not cover many of your Puppeteer needs, it's good to keep more than one tool in your belt.

Wrapping up

In this article, I've presented a handful of Puppeteer antipatterns to be on the lookout for. We hope that a critical examination of them will help keep your Puppeteer code clean, fast, reliable and easy to maintain. As the tool grows, I'll be curious to see how these patterns evolve along with it.

Keep in mind that these guidelines are rules-of-thumb and might need to be broken from time to time. The key is to be aware of the tradeoffs when using them.

Happy automating!

This article is current as of Puppeteer version 13.5.1.

Originally published at SerpApi by Greg Gorlen at April 1, 2022.